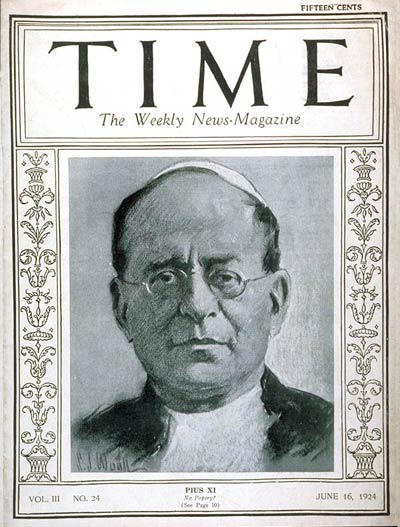

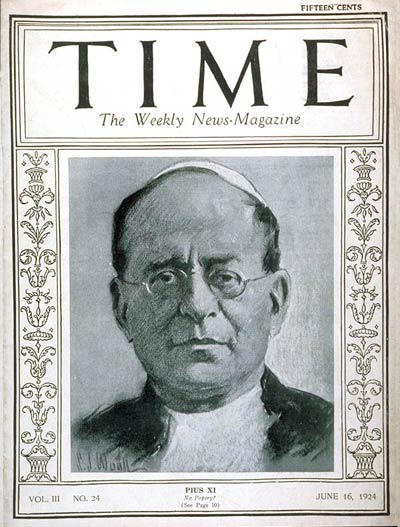

Pius XI on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pope Pius XI (; born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, ; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939) was head of the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

from 6 February 1922 until his death in February 1939. He was also the first sovereign of the

Vatican City State

Vatican City, officially the Vatican City State (; ), is a Landlocked country, landlocked sovereign state and city-state; it is enclaved within Rome, the capital city of Italy and Bishop of Rome, seat of the Catholic Church. It became inde ...

upon its creation on 11 February 1929.

Pius XI issued numerous

encyclical

An encyclical was originally a circular letter sent to all the churches of a particular area in the ancient Roman Church. At that time, the word could be used for a letter sent out by any bishop. The word comes from the Late Latin (originally fr ...

s, including ''

Quadragesimo anno

''Quadragesimo anno'' () (Latin for "In the 40th Year") is an encyclical issued by Pope Pius XI on 15 May 1931, 40 years after Leo XIII's encyclical '' Rerum novarum'', further developing Catholic social teaching. Unlike Leo XIII, who addre ...

'' on the 40th anniversary of

Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII (; born Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2March 181020July 1903) was head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 until his death in July 1903. He had the fourth-longest reign of any pope, behind those of Peter the Ap ...

's groundbreaking social encyclical ''

Rerum novarum

''Rerum novarum'', or ''Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor'', is an encyclical issued by Pope Leo XIII on 15 May 1891. It is an open letter, passed to all Catholic patriarchs, primates, archbishops, and bishops, which addressed the condi ...

'', highlighting the capitalistic greed of international finance, the dangers of

atheistic

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

/

communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, and

social justice

Social justice is justice in relation to the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society where individuals' rights are recognized and protected. In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has of ...

issues, and ''

Quas primas

(from Latin: "In the first") is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI. Promulgated on December 11, 1925, it introduced the Feast of Christ the King.

Purpose and content

''Quas primas'' followed Pius's initial encyclical, ''Ubi arcano Dei consilio'', w ...

'', establishing the

feast of Christ the King

The Solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe, commonly referred to as the Feast of Christ the King, Christ the King Sunday or Reign of Christ Sunday, is a feast in the liturgical year which emphasises the true kingship of Christ ...

in response to

anti-clericalism

Anti-clericalism is opposition to clergy, religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historically, anti-clericalism in Christian traditions has been opposed to the influence of Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secul ...

. The encyclical ''Studiorum ducem'', promulgated 29 June 1923, was written on the occasion of the 6th centenary of the canonization of

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

, whose thought is acclaimed as central to Catholic philosophy and theology. The encyclical also singles out the

Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas

The Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas (PUST), also known as the ''Angelicum'' or ''Collegio Angelico'' (in honor of its patron, the ''Doctor Angelicus'' Thomas Aquinas), is a pontifical university located in the historic center of R ...

, ''Angelicum'' as the preeminent institution for the teaching of Aquinas: "ante omnia Pontificium Collegium Angelicum, ubi Thomam tamquam domi suae habitare dixeris" (before all others the Pontifical Angelicum College, where Thomas can be said to dwell). The encyclical ''

Casti connubii

''Casti connubii'' (Latin: "of chaste wedlock") is a papal encyclical promulgated by Pope Pius XI on 31 December 1930 in response to the Lambeth Conference of the Anglican Communion. It stressed the sanctity of marriage, prohibited Catholics ...

'' promulgated on 31 December 1930 prohibited Catholics from using

contraception

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

.

To establish or maintain the position of the Catholic Church, Pius XI concluded a record number of

concordat

A concordat () is a convention between the Holy See and a sovereign state that defines the relationship between the Catholic Church and the state in matters that concern both,René Metz, ''What is Canon Law?'' (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1960 ...

s, including the ''Reichskonkordat'' with Nazi Germany">Reichskonkordat"> ...

s, including the ''Reichskonkordat'' with Nazi Germany, and he condemned their betrayals four years later in the encyclical ''

Mit brennender Sorge

''Mit brennender Sorge'' ( , in English "With deep it. 'burning'anxiety") is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, issued during the Nazi era on 10 March 1937 (but bearing a date of Passion Sunday, 14 March)."Church and state through the centu ...

'' ("With Burning Concern"). During his pontificate, the longstanding hostility with the Italian government over the status of the papacy and the Church in Italy was successfully resolved in the Lateran Treaty of 1929. He was unable to stop the persecution of the Church and the killing of clergy in

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

,

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, and the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. He canonized saints including

Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, theologian, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VII ...

,

Peter Canisius

Peter Canisius (; 8 May 1521 – 21 December 1597) was a Dutch Jesuit priest known for his strong support for the Catholic faith during the Protestant Reformation in Germany, Austria, Bohemia, Moravia, Switzerland and the British Isles. The ...

,

Bernadette of Lourdes

Bernadette Soubirous, Sisters of Charity of Nevers, SCN (; ; ; 7 January 184416 April 1879), also known as Bernadette of Lourdes (religious name, in religion Sister Marie-Bernarde), was a miller's daughter from Lourdes ( in Occitan), in the Dep ...

, and

Don Bosco

John Melchior Bosco, SDB (; ; 16 August 181531 January 1888), popularly known as Don Bosco or Dom Bosco ( IPA: ), was an Italian Catholic priest, educator and writer. While working in Turin, where the population suffered many of the ill eff ...

. He beatified and canonized

Thérèse de Lisieux

Therese or Thérèse is a variant of the feminine given name Teresa. It may refer to:

Persons

Therese

* Duchess Therese of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1773–1839), member of the House of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and a Duchess of Mecklenburg

* Therese of ...

, for whom he held special reverence, and gave

equivalent canonization

Through an equivalent canonization or equipollent canonization (Latin: ) a pope can choose to relinquish the judicial processes, formal attribution of miracles, and scientific examinations that are typically involved in the canonization of a saint ...

to

Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

, naming him a

Doctor of the Church

Doctor of the Church (Latin: ''doctor'' "teacher"), also referred to as Doctor of the Universal Church (Latin: ''Doctor Ecclesiae Universalis''), is a title given by the Catholic Church to saints recognized as having made a significant contribut ...

due to his writings' spiritual power. He took a strong interest in fostering the participation of laypeople throughout the Church, especially in the

Catholic Action

Catholic Action is a movement of Catholic laity, lay people within the Catholic Church which advocates for increased Catholic influence on society. Catholic Action groups were especially active in the nineteenth century in historically Catholic cou ...

movement. The end of his pontificate was dominated by speaking out against Hitler and Mussolini, and defending the Catholic Church from intrusions into its life and education.

Pius XI died on 10 February 1939 in the

Apostolic Palace

The Apostolic Palace is the official residence of the Pope, the head of the Catholic Church, located in Vatican City. It is also known as the Papal Palace, the Palace of the Vatican and the Vatican Palace. The Vatican itself refers to the build ...

and was buried in the Papal Grotto of

Saint Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican (), or simply St. Peter's Basilica (; ), is a church of the Italian Renaissance architecture, Italian High Renaissance located in Vatican City, an independent microstate enclaved within the cit ...

. In the course of excavating space for his tomb,

two levels of burial grounds were uncovered that revealed bones now venerated as

the bones of St. Peter.

Early life and career

Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti was born in

Desio

Desio () is a (municipality) in the province of Monza and Brianza, in the Italian region of Lombardy.

History

In 1277 it was the location of the battle between the Visconti and della Torre families for the rule of Milan. On 24 February 1924, ...

, in the

province of Milan

The province of Milan () was a province in the Lombardy region of Italy. Its capital was the city of Milan. The area of the former province is highly urbanized, with more than 2,000 inhabitants/km2, the third-highest population density among Ital ...

, in 1857, the son of the owner of a

silk

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is most commonly produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), c ...

factory. His parents were Francesco Antonio

Ratti Ratti may refer to:

* Ratti (unit), traditional Indian unit of mass measurement

* Ratti Gali Lake, an alpine glacial lake located in Neelum Valley, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan

* Ratti (surname), Italian surname

* Ratti family, Italian family

{{disambigu ...

(1823–1881) and his wife Angela Teresa née Galli-Cova (1832–1918); his siblings were Carlo (1853–1906), Fermo (1854–1929), Edoardo (1855–1896), Camilla (1860–1946), and Cipriano. He was ordained a priest in 1879 and was selected for a life of academic studies within the Church. He obtained three doctorates (in

philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

,

canon law

Canon law (from , , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical jurisdiction, ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its membe ...

, and

theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

) at the

Gregorian University

Pontifical Gregorian University (; also known as the Gregorian or Gregoriana), is a private pontifical university in Rome, Italy.

The Gregorian originated as a part of the Roman College, founded in 1551 by Ignatius of Loyola, and included all ...

in

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, and from 1882 to 1888 was a professor at a seminary in

Padua

Padua ( ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Veneto, northern Italy, and the capital of the province of Padua. The city lies on the banks of the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice and southeast of Vicenza, and has a population of 20 ...

. His scholarly speciality was as an expert

paleographer

Palaeography ( UK) or paleography ( US) (ultimately from , , 'old', and , , 'to write') is the study and academic discipline of historical writing systems. It encompasses the historicity of manuscripts and texts, subsuming deciphering and dati ...

, a student of ancient and medieval Church manuscripts. In 1888, he was transferred from seminary teaching to the

Ambrosian Library

The Biblioteca Ambrosiana is a historic library in Milan, Italy, also housing the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, the Ambrosian art gallery. Named after Ambrose, the patron saint of Milan, it was founded in 1609 by Cardinal Federico Borromeo, whose agen ...

in

Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

, where he worked until 1911.

During this time, Ratti edited and published an edition of the

Ambrosian Missal

A missal is a liturgical book containing instructions and texts necessary for the celebration of Mass throughout the liturgical year. Versions differ across liturgical tradition, period, and purpose, with some missals intended to enable a priest ...

(the rite of Mass used in a wide territory in northern Italy, coinciding above all with the

diocese of Milan

The Archdiocese of Milan (; ) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or archdiocese of the Catholic Church in Italy which covers the areas of Milan, Monza, Lecco and Varese. It has long maintained its own Latin liturgical rite usage, the Ambro ...

). He also engaged in research and writing on the life and works of the reforming Archbishop of Milan,

Charles Borromeo

Charles Borromeo (; ; 2 October 1538 – 3 November 1584) was an Catholic Church in Italy, Italian Catholic prelate who served as Archdiocese of Milan, Archbishop of Milan from 1564 to 1584. He was made a Cardinal (Catholicism), cardinal in 156 ...

. Ratti became head of the Ambrosian Library in 1907 and undertook a thorough programme of restoration and reclassification of its collections. In his spare time, he was an avid

mountaineer

Mountaineering, mountain climbing, or alpinism is a set of outdoor activities that involves ascending mountains. Mountaineering-related activities include traditional outdoor climbing, skiing, and traversing via ferratas that have become sports ...

, reaching the summits of

Monte Rosa

Monte Rosa (; ; ; or ; ) is a mountain massif in the eastern part of the Pennine Alps, on the border between Italy (Piedmont and Aosta Valley) and Switzerland (Valais). The highest peak of the massif, amongst several peaks of over , is the D ...

, the

Matterhorn

The , ; ; ; or ; ; . is a mountain of the Alps, straddling the Main chain of the Alps, main watershed and border between Italy and Switzerland. It is a large, near-symmetric pyramidal peak in the extended Monte Rosa area of the Pennine Alps, ...

,

Mont Blanc

Mont Blanc (, ) is a mountain in the Alps, rising above sea level, located right at the Franco-Italian border. It is the highest mountain in Europe outside the Caucasus Mountains, the second-most prominent mountain in Europe (after Mount E ...

, and

Presolana. A scholar-athlete pope was not seen again until

John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

. In 1911, Ratti was appointed by

Pope Pius X

Pope Pius X (; born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto; 2 June 1835 – 20 August 1914) was head of the Catholic Church from 4 August 1903 to his death in August 1914. Pius X is known for vigorously opposing Modernism in the Catholic Church, modern ...

Vice-Prefect of the

Vatican Library

The Vatican Apostolic Library (, ), more commonly known as the Vatican Library or informally as the Vat, is the library of the Holy See, located in Vatican City, and is the city-state's national library. It was formally established in 1475, alth ...

, and in 1914 was promoted to Prefect.

Nuncio to Poland and expulsion

In 1918,

Pope Benedict XV

Pope Benedict XV (; ; born Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista della Chiesa, ; 21 November 1854 – 22 January 1922) was head of the Catholic Church from 1914 until his death in January 1922. His pontificate was largely overshadowed by World War I a ...

(1914–1922) appointed Ratti to what was in effect a diplomatic post, as

apostolic visitor

In the Catholic Church, an apostolic visitor (or ''Apostolic Visitator''; Italian: Visitatore apostolico) is a papal representative with a transient mission to perform a canonical visitation of relatively short duration. The visitor is deputed ...

(an unofficial papal representative) in

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

. In the aftermath of World War I, a Polish state was restored, though the process was in practice incomplete, since the territory was still under the effective control of

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

. In October 1918, Benedict was the first head of state to congratulate the Polish people on the occasion of the restoration of their independence.

[Schmidlin III, 306.] In March 1919, he appointed ten new bishops and on 6 June 1919 reappointed Ratti, this time to the rank of

papal nuncio

An apostolic nuncio (; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international organization. A nuncio is a ...

and on 3 July appointed him a

titular archbishop

A titular bishop in various churches is a bishop who is not in charge of a diocese.

By definition, a bishop is an "overseer" of a community of the faithful, so when a priest is ordained a bishop, the tradition of the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox an ...

.

Ratti was consecrated as a

bishop

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of di ...

on 28 October 1919.

According to German theologian

Joseph Schmidlin

Joseph is a common male name, derived from the Hebrew (). "Joseph" is used, along with " Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the modern-day Nordic count ...

's ''Papstgeschichte der Neuesten Zeit'', Benedict and Ratti repeatedly cautioned Polish authorities against persecuting Lithuanian and

Ruthenian clergy.

[Schmidlin III, 307.] During the Bolshevik advance against

Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

during the

Polish-Soviet War, Benedict asked for worldwide public prayers for Poland, while Ratti was the only foreign diplomat who refused to flee Warsaw when the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

was approaching the city in August 1920. On 11 June 1921, Benedict asked Ratti to deliver his message to the Polish episcopate, warning against political misuses of spiritual power, urging peaceful coexistence with neighboring peoples, and saying that "love of country has its limits in justice and obligations".

Ratti intended to work for

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

by building bridges to men of goodwill in the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, even to shedding his blood for Russia.

[Stehle, 25.] But Benedict needed Ratti as a diplomat, not a martyr, and forbade his traveling to the USSR despite his being the official papal delegate for Russia.

The nuncio's continued contacts with Russians did not generate much sympathy for him within Poland at the time. After Benedict sent Ratti to

Silesia

Silesia (see names #Etymology, below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at 8, ...

to forestall potential political agitation within the Polish Catholic clergy,

Ratti was asked to leave Poland. On 20 November, when German Cardinal

Adolf Bertram

Adolf Bertram (14 March 1859 – 6 July 1945) was archbishop of Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland) and a cardinal of the Catholic Church.

Early life

Adolf Bertram was born in Hildesheim, Royal Prussian Province of Hanover (now Lower Saxony), Germa ...

announced a papal ban on all political activities of clergymen, calls for Ratti's expulsion climaxed.

"While he tried honestly to show himself as a friend of Poland, Warsaw forced his departure, after his neutrality in

Silesian voting was questioned" by Germans and Poles. Nationalistic Germans objected to the Polish nuncio supervising local elections, and patriotic Poles were upset because he curtailed political action among the clergy.

[Schmidlin IV, 15.]

Elevation to the papacy

In the

consistory

Consistory is the anglicized form of the consistorium, a council of the closest advisors of the Roman emperors. It can also refer to:

*A papal consistory, a formal meeting of the Sacred College of Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church

*Consistor ...

of 3 June 1921, Benedict XV created three new cardinals, including Ratti, who was appointed

Archbishop of Milan

The Archdiocese of Milan (; ) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or archdiocese of the Catholic Church in Italy which covers the areas of Milan, Monza, Lecco and Varese. It has long maintained its own Latin liturgical rite usage, the Amb ...

simultaneously. Benedict told them, "Well, today I gave you the red hat, but soon it will be white for one of you."

[Fontenelle, 40.] After the Vatican celebration, Ratti went to the Benedictine monastery at

Monte Cassino

The Abbey of Monte Cassino (today usually spelled Montecassino) is a Catholic Church, Catholic, Benedictines, Benedictine monastery on a rocky hill about southeast of Rome, in the Valle Latina, Latin Valley. Located on the site of the ancient ...

for a retreat to prepare spiritually for his new role. He accompanied Milanese pilgrims to

Lourdes

Lourdes (, also , ; ) is a market town situated in the Pyrenees. It is part of the Hautes-Pyrénées department in the Occitanie region in southwestern France. Prior to the mid-19th century, the town was best known for its Château fort, a ...

in August 1921.

Ratti received a tumultuous welcome on a visit to his home town of

Desio

Desio () is a (municipality) in the province of Monza and Brianza, in the Italian region of Lombardy.

History

In 1277 it was the location of the battle between the Visconti and della Torre families for the rule of Milan. On 24 February 1924, ...

, and was enthroned in Milan on 8 September. On 22 January 1922, Benedict XV died unexpectedly of

pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

.

At the conclave to choose a new pope, the longest of the 20th century, the

College of Cardinals

The College of Cardinals (), also called the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. there are cardinals, of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Appointed by the pope, ...

was divided into two factions, one led by

Rafael Merry del Val

Rafael Merry del Val y Zulueta, (10 October 1865 – 26 February 1930) was a Spanish Catholic bishop, Vatican official, and cardinal.

Before becoming a cardinal, he served as the secretary of the papal conclave of 1903 that elected Pope Pius ...

favoring the policies and style of Pius X and the other favoring those of Benedict XV led by

Pietro Gasparri

Pietro Gasparri (5 May 1852 – 18 November 1934) was a Roman Catholic cardinal, diplomat and politician in the Roman Curia and the signatory of the Lateran Pacts. He served also as Cardinal Secretary of State under Popes Benedict XV and Pope ...

.

Gasparri approached Ratti before voting began on the third day and told him he would urge his supporters to switch their votes to Ratti, who was shocked to hear this. When it became clear that neither Gasparri nor del Val could win, the cardinals approached Ratti, thinking him a compromise candidate not identified with either faction. Cardinal

Gaetano de Lai approached Ratti and was believed to have said: "We will vote for Your Eminence if Your Eminence will promise that you will not choose Cardinal Gasparri as your secretary of state". Ratti is said to have responded: "I hope and pray that among so highly deserving cardinals the Holy Spirit selects someone else. If I am chosen, it is indeed Cardinal Gasparri whom I will take to be my secretary of state".

Ratti was elected on the conclave's 14th ballot on 6 February 1922 and took the name Pius XI, explaining that Pius IX was the pope of his youth and Pius X had appointed him head of the Vatican Library. It was rumored that immediately after the election, he decided to appoint Pietro Gasparri as his

Cardinal Secretary of State

The Secretary of State of His Holiness (; ), also known as the Cardinal Secretary of State or the Vatican Secretary of State, presides over the Secretariat of State of the Holy See, the oldest and most important dicastery of the Roman Curia. Th ...

. When asked if he accepted his election, Ratti was said to have replied: "In spite of my unworthiness, of which I am deeply aware, I accept". He went on to say that his choice in papal name was because "Pius is a name of peace".

After the dean Cardinal

Vincenzo Vannutelli

Vincenzo Vannutelli (5 December 1836 – 9 July 1930) was an Italian prelate of the Catholic Church. He spent his career in the foreign service of the Holy See and was made a cardinal in 1890.

At his death he was the oldest member of the Coll ...

asked if he assented to the election, Ratti paused in silence for two minutes, according to Cardinal

Désiré-Joseph Mercier

Désiré Félicien François Joseph Mercier (21 November 1851 – 23 January 1926) was a Belgian Catholic prelate who served as Archbishop of Mechelen from 1906 until his death in 1926. A Thomist scholar, he had several of his works translated i ...

. The Hungarian cardinal

János Csernoch later commented: "We made Cardinal Ratti pass through the fourteen stations of the Via Crucis and then we left him alone on Calvary".

As Pius XI's first act as pope, he revived the traditional public blessing from the balcony, ''

Urbi et Orbi'' ("to the city and to the world"), abandoned by his predecessors since the

loss of Rome to the Italian state in 1870. This suggested his openness to a rapprochement with the government of Italy. Less than a month later, considering that all four cardinals from the Western Hemisphere had been unable to participate in his election, he issued ''

Cum proxime'' to allow the College of Cardinals to delay the start of a conclave for as long as 18 days following the death of a pope.

Public teaching: "The Peace of Christ in the Reign of Christ"

Pius XI's first encyclical as pope was directly related to his aim of Christianizing all aspects of increasingly secular societies. ''

Ubi arcano'', promulgated in December 1922, inaugurated the "Catholic Action" movement.

Similar goals were in evidence in two encyclicals of 1929 and 1930. ''Divini illius magistri'' ("That Divine Teacher's") (1929) made clear the need for Christian over secular education. ''

Casti connubii

''Casti connubii'' (Latin: "of chaste wedlock") is a papal encyclical promulgated by Pope Pius XI on 31 December 1930 in response to the Lambeth Conference of the Anglican Communion. It stressed the sanctity of marriage, prohibited Catholics ...

'' ("Chaste Wedlock") (1930) praised Christian marriage and family life as the basis for any good society; it condemned artificial means of contraception, but acknowledged the unitive aspect of intercourse:

* ...

y use whatsoever of matrimony exercised in such a way that the act is deliberately frustrated in its natural power to generate life is an offense against the law of God and of nature, and those who indulge in such are branded with the guilt of a grave sin.

* ....Nor are those considered as acting against nature who in the married state use their right in the proper manner although on account of natural reasons either of time or of certain defects, new life cannot be brought forth. For in matrimony as well as in the use of the matrimonial rights there are also secondary ends, such as mutual aid, the cultivating of mutual love, and the quieting of concupiscence which husband and wife are not forbidden to consider so long as they are subordinated to the primary end and so long as the intrinsic nature of the act is preserved.

Political teachings

In contrast to some of his 19th-century predecessors who favored monarchy and dismissed democracy, Pius XI took a pragmatic approach toward different forms of government. In his encyclical ''

Dilectissima Nobis

''Dilectissima Nobis'' ("On Oppression of the Church of Spain") is an encyclical issued by Pope Pius XI on 3 June 1933, in which he decried persecution of the Church in Spain, citing the expropriation of all Church buildings, episcopal residences ...

'' (1933), in which he addressed the situation of the Church in

Republican Spain

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of democratic government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931 after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII. It was dissol ...

, he proclaimed,

Social teachings

Pius XI argued for a reconstruction of economic and political life on the basis of religious values. ''

Quadragesimo anno

''Quadragesimo anno'' () (Latin for "In the 40th Year") is an encyclical issued by Pope Pius XI on 15 May 1931, 40 years after Leo XIII's encyclical '' Rerum novarum'', further developing Catholic social teaching. Unlike Leo XIII, who addre ...

'' (1931) was written to mark 'forty years' since

Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII (; born Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2March 181020July 1903) was head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 until his death in July 1903. He had the fourth-longest reign of any pope, behind those of Peter the Ap ...

's (1878–1903) encyclical ''

Rerum novarum

''Rerum novarum'', or ''Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor'', is an encyclical issued by Pope Leo XIII on 15 May 1891. It is an open letter, passed to all Catholic patriarchs, primates, archbishops, and bishops, which addressed the condi ...

'', and restated that encyclical's warnings against both socialism and unrestrained capitalism, as enemies to human freedom and dignity. Pius XI instead envisioned an economy based on cooperation and solidarity.

In ''Quadragesimo anno'', Pius XI wrote that social and economic issues are vital to the Church not from a technical point of view but morally and ethically. Ethical considerations include the nature of private property

[''Quadragesimo anno'', 44–52.] in terms of its functions for society and the development of the individual.

[''Quadragesimo anno'', 114–115.] He defined fair wages and called international capitalism materially and spiritually exploitative.

Gender roles

Pius XI wrote that mothers should work primarily

within the home, or in its immediate vicinity, and concentrate on household duties. He argued that every effort in society must be made for fathers to make high enough wages that it never becomes necessary for mothers to work. Forced dual-income situations in which mothers work he called an "intolerable abuse".

[''Quadragesimo Anno'', 71.] Pius also criticized

egalitarianist stances, describing modern attempts to "

liberate women" as a "crime". He wrote that attempts to liberate women from their husbands are a "false liberty and unnatural equality" and that the true emancipation of women "belongs to the noble office of a Christian woman and wife."

Private property

The Church has a role in discussing the issues related to the social order. Social and economic issues are vital to it not from a technical point of view but morally and ethically. Ethical considerations include the nature of private property.

Within the Catholic Church, several conflicting views had developed. Pius declared private property essential for individual development and freedom, and said that those who deny private property also deny personal freedom and development. He also said that private property has a social function and loses its morality if it is not subordinated to the common good, and governments have a right to redistribution policies. In extreme cases, he granted the state a right to expropriate private property.

Capital and labor

A related issue, said Pius, is the relation between capital and labor and the determination of fair wages.

[''Quadragesimo anno'', 63–75.] Pius develops the following ethical mandate: The Church considers it a perversion of industrial society to have developed sharp opposite camps based on income. He welcomes all attempts to alleviate these differences. Three elements determine a fair wage: the worker's family, the economic condition of the enterprise, and the economy as a whole. The family has an innate right to development, but this is possible only within the framework of a functioning economy and a sound enterprise. Thus, Pius concludes that cooperation and not conflict is a necessary condition, given the interdependence of the parties involved.

Social order

Pius XI believed that industrialization results in less freedom at the individual and communal level because numerous free social entities get absorbed by larger ones. The society of individuals becomes the mass class-society. People are much more interdependent than in ancient times, and become egoistic or class-conscious in order to save some freedom for themselves. The pope demands more solidarity, especially between employers and employees, through new forms of cooperation and communication. Pius displays an unfavorable view of capitalism, especially anonymous international finance markets. He identifies certain dangers for small and medium-size enterprises that have insufficient access to capital markets and are squeezed or destroyed by larger ones. He warns that capitalist interests can become a danger for nations, which could be reduced to "chained slaves of individual interests".

Pius XI was the first Pope to use the power of modern communications technology in evangelizing the wider world. He established

Vatican Radio

Vatican Radio (; ) is the official broadcasting service of Vatican City.

Established in 1931 by Guglielmo Marconi, today its programs are offered in 47 languages, and are sent out on short wave, DRM, medium wave, FM, satellite and the Internet. ...

in 1931, and was the first Pope to broadcast on radio.

Internal Church affairs and ecumenism

In his management of the Church's internal affairs, Pius XI mostly continued the policies of his predecessor. Like

Benedict XV

Pope Benedict XV (; ; born Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista della Chiesa, ; 21 November 1854 – 22 January 1922) was head of the Catholic Church from 1914 until his death in January 1922. His pontificate was largely overshadowed by World War I a ...

, he emphasized spreading Catholicism in Africa and Asia and training native clergy in those territories. He ordered every religious order to devote some of its personnel and resources to missionary work.

Pius XI continued the approach of Benedict XV on the issue of how to deal with the threat of

modernism

Modernism was an early 20th-century movement in literature, visual arts, and music that emphasized experimentation, abstraction, and Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy), subjective experience. Philosophy, politics, architecture, and soc ...

in Catholic theology. He was thoroughly orthodox theologically and had no sympathy with modernist ideas that relativized fundamental Catholic teachings. He condemned modernism in his writings and addresses. But his opposition to modernist theology was by no means a rejection of new scholarship within the Church, as long as it was developed within the framework of orthodoxy and compatible with the Church's teachings. Pius XI was interested in supporting serious scientific study within the Church, establishing the

Pontifical Academy of the Sciences in 1936. In 1928 he formed the Gregorian Consortium of universities in Rome administered by the

Society of Jesus

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rome. It was founded in 1540 ...

, fostering closer collaboration between their

Gregorian University

Pontifical Gregorian University (; also known as the Gregorian or Gregoriana), is a private pontifical university in Rome, Italy.

The Gregorian originated as a part of the Roman College, founded in 1551 by Ignatius of Loyola, and included all ...

,

Biblical Institute, and

Oriental Institute.

Pius XI strongly encouraged devotion to the

Sacred Heart

The Most Sacred Heart of Jesus () is one of the most widely practised and well-known Catholic devotions, wherein the heart of Jesus Christ is viewed as a symbol of "God's boundless and passionate love for mankind". This devotion to Christ is p ...

in his encyclical ''

Miserentissimus Redemptor

''Miserentissimus Redemptor'' (English language, English: "Most Merciful Redeemer") is the title of an encyclical written by Pope Pius XI, promulgated on May 8, 1928, on the Reparation (theology), theology of reparation to the Sacred Heart.

Co ...

'' (1928).

Pius XI was the first pope to directly address the

Christian ecumenical movement. Like Benedict XV he was interested in achieving reunion with the

Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

(failing that, he determined to give special attention to the

Eastern Catholic

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also known as the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous ('' sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

churches). He also allowed the dialogue between Catholics and

Anglicans

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

that had been planned during Benedict XV's pontificate to take place at

Mechelen

Mechelen (; ; historically known as ''Mechlin'' in EnglishMechelen has been known in English as ''Mechlin'', from where the adjective ''Mechlinian'' is derived. This name may still be used, especially in a traditional or historical context. T ...

, but these enterprises were firmly aimed at actually reuniting with the Catholic Church other Christians who basically agreed with Catholic doctrine, bringing them back under papal authority. To the broad pan-Protestant ecumenical movement he took a less favorable attitude.

He rejected, in his 1928 encyclical ''

Mortalium animos'', the idea that Christian unity could be attained by establishing a broad federation of many bodies holding conflicting doctrines; rather, the Catholic Church was the true Church of Christ. "The union of Christians can only be promoted by promoting the return to the one true Church of Christ of those who are separated from it, for in the past they have unhappily left it." The pronouncement also prohibited Catholics from joining groups that encouraged interfaith discussion without distinction.

The next year, the Vatican was successful in lobbying the

Mussolini regime to require Catholic religious education in all schools, even those with a majority of Protestants or Jews. The Pope expressed his "great pleasure" with the move.

In 1934, the Fascist government at the Vatican's urging agreed to expand the prohibition of public gatherings of Protestants to include private worship in homes.

Activities

Beatifications and canonizations

Pius XI canonized 34 saints during his pontificate, including

Bernadette Soubirous

Bernadette Soubirous, Sisters of Charity of Nevers, SCN (; ; ; 7 January 184416 April 1879), also known as Bernadette of Lourdes (religious name, in religion Sister Marie-Bernarde), was a miller's daughter from Lourdes ( in Occitan), in the Dep ...

(1933),

Thérèse of Lisieux

Thérèse of Lisieux (born Marie Françoise-Thérèse Martin; 2 January 1873 – 30 September 1897), religious name, in religion Therese of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face, was a French Discalced Carmelites, Discalced Carmelite who is widely v ...

(1925),

John Vianney

John Vianney (born Jean-Marie Vianney and later Jean-Marie-Baptiste Vianney; 8 May 1786 – 4 August 1859) was a Catholic Church in France, French Catholic priest often referred to as the ''Curé d'Ars'' ("the parish priest of Ars"). He is known ...

(1925),

John Fisher

John Fisher (c. 19 October 1469 – 22 June 1535) was an English Catholic prelate who served as Bishop of Rochester from 1504 to 1535 and as chancellor of the University of Cambridge. He is honoured as a martyr and saint by the Catholic Chu ...

and

Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, theologian, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VII ...

(1935), and

John Bosco

John Melchior Bosco, Salesians of Don Bosco, SDB (; ; 16 August 181531 January 1888), popularly known as Don Bosco or Dom Bosco (International Phonetic Alphabet, IPA: ), was an Italian Catholic priest, educator and writer. While working in Tu ...

(1934). He also beatified 464 of the faithful, including

Pierre-René Rogue (1934) and

Noël Pinot

Noël Pinot (9 December 1747 – 21 February 1794) was a French Refractory clergy, refractory priest who was guillotined during the War in the Vendée. He was beatified by the Catholic Church and considered a martyr.

Biography

Born in Angers ...

(1926).

Pius XI also declared certain saints to be

Doctors of the Church

Doctor of the Church (Latin: ''doctor'' "teacher"), also referred to as Doctor of the Universal Church (Latin: ''Doctor Ecclesiae Universalis''), is a title given by the Catholic Church to saints recognized as having made a significant contribut ...

:

*

Peter Canisius

Peter Canisius (; 8 May 1521 – 21 December 1597) was a Dutch Jesuit priest known for his strong support for the Catholic faith during the Protestant Reformation in Germany, Austria, Bohemia, Moravia, Switzerland and the British Isles. The ...

(21 May 1925)

*

John of the Cross

St. John of the Cross (; ; né Juan de Yepes y Álvarez; 24 June 1542 – 14 December 1591) was a Spanish Roman Catholic priest, mystic, and Carmelite friar of ''Converso'' ancestry. He is a major figure of the Counter-Reformation in Spain, ...

(24 August 1926; naming him "''Doctor mysticus''" or "Mystical Doctor")

*

Robert Bellarmine

Robert Bellarmine (; ; 4 October 1542 – 17 September 1621) was an Italian Jesuit and a cardinal of the Catholic Church. He was canonized a saint in 1930 and named Doctor of the Church, one of only 37. He was one of the most important figure ...

(17 September 1931)

*

Albert the Great

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

(16 December 1931; naming him "''Doctor universalis''" or "Universal Doctor")

Consistories

Pius XI created 76 cardinals in 17 consistories, including

August Hlond

August Hlond, SDB (5 July 1881 – 22 October 1948) was a Polish Salesian prelate who served as Archbishop of Poznań and Gniezno and as Primate of Poland. He was later appointed Archbishop of Gniezno and Warsaw and was made a cardinal of ...

(1927),

Alfredo Ildefonso Schuster

Alfredo Ildefonso Schuster, (, ; born Alfredo Ludovico Schuster; 18 January 1880 – 30 August 1954) was an Italian Catholic prelate and professed member of the Benedictines who served as the Archbishop of Milan from 1929 until his death. He ...

(1929),

Raffaele Rossi (1930),

Elia Dalla Costa

Elia Dalla Costa (14 May 1872 – 22 December 1961) was an Italian people, Italian Roman Catholic Church, Roman Catholic prelate and Cardinal (Catholicism), cardinal who served as the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Florence, Archbishop of ...

(1933), and

Giuseppe Pizzardo

Giuseppe Pizzardo (13 July 1877 – 1 August 1970) was an Italian cardinal of the Catholic Church who served as prefect of the Congregation for Seminaries and Universities from 1939 to 1968, and secretary of the Holy Office from 1951 to 195 ...

(1937). One of those was his successor, Eugenio Pacelli, who became

Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII (; born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli; 2 March 18769 October 1958) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death on 9 October 1958. He is the most recent p ...

. Pius XI in fact believed that Pacelli would be his successor and dropped many hints that this was his hope. On one such occasion at a consistory for new cardinals on 13 December 1937, while posing with the new cardinals, Pius XI pointed to Pacelli and told them: "He'll make a good pope!"

Pius XI also accepted the resignation of a cardinal from the cardinalate in 1927: the Jesuit

Louis Billot

Louis Billot (12 January 1846 in Sierck-les-Bains, Moselle (department), Moselle, France – 18 December 1931 in Ariccia, Latium, Italy) was a French Jesuit priest and Theology, theologian. He became a cardinal in 1911 and resigned from that stat ...

.

The pope deviated from the usual practice of naming cardinals in collective consistories, opting instead for smaller and more frequent consistories, with some of them being less than six months apart. Unlike his predecessors, he increased the number of non-Italian cardinals.

In 1923, Pius XI wanted to appoint Ricardo Sanz de Samper y Campuzano (

majordomo

A majordomo () is a person who speaks, makes arrangements, or takes charge for another. Typically, this is the highest (''major'') person of a household (''domūs'' or ''domicile'') staff, a head servant who acts on behalf of the owner of a larg ...

in the

Papal Household

The papal household or pontifical household (usually not capitalized in the media and other nonofficial use, ), called until 1968 the Papal Court (''Aula Pontificia''), consists of dignitaries who assist the pope in carrying out particular ceremon ...

) to the College of Cardinals but was forced to abandon the idea when King

Alfonso XIII

Alfonso XIII (Spanish language, Spanish: ''Alfonso León Fernando María Jaime Isidro Pascual Antonio de Borbón y Habsburgo-Lorena''; French language, French: ''Alphonse Léon Ferdinand Marie Jacques Isidore Pascal Antoine de Bourbon''; 17 May ...

of Spain insisted that the pope appoint cardinals from

South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

despite the fact that Sanz hailed from

Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country primarily located in South America with Insular region of Colombia, insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuel ...

. Since Pius XI did not want to appear to be influenced by political considerations, he chose in the December 1923 consistory to name no South American cardinals at all. According to an article by the historian Monsignor Vicente Cárcel y Ortí, a 1928 letter from Alfonso XIII asked the pope to restore

Valencia

Valencia ( , ), formally València (), is the capital of the Province of Valencia, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, the same name in Spain. It is located on the banks of the Turia (r ...

as a cardinalitial see and appoint its archbishop, Prudencio Melo y Alcalde, a cardinal. Pius XI responded that he could not do so because Spain already had the habitual number of cardinals (set at four) with two of them fixed (

Toledo

Toledo most commonly refers to:

* Toledo, Spain, a city in Spain

* Province of Toledo, Spain

* Toledo, Ohio, a city in the United States

Toledo may also refer to:

Places Belize

* Toledo District

* Toledo Settlement

Bolivia

* Toledo, Or ...

and

Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

) and the other two variable. Pius XI recommended that Alfonso XIII wait for a future occasion, but he never did make the archbishop a cardinal, and not until 2007 was the diocese given a cardinal archbishop. In December 1935, the pope intended to appoint the Jesuit priest

Pietro Tacchi Venturi

Pietro Tacchi Venturi (; 18 March 1861–19 March 1956)''New York Times''. 1956, March 19. "Obituary 3--No Title". p. 31. was an antisemitic Jesuit priest and historian who served as the unofficial liaison between Benito Mussolini, the Fascist ...

a cardinal, but abandoned the idea given that the

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

government would have regarded the move as a friendly gesture toward

Fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

since the priest and

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

were considered to be close.

International relations

The pontificate of Pius XI coincided with the early aftermath of the First World War. Many of the old European monarchies had been swept away and a new and precarious order formed across the continent. In the East, the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

arose. In

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, the

Fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

dictator

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

took power, while in Germany, the fragile

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

collapsed with the Nazi seizure of power.

[Encyclopædia Britannica Online: Pius XI; web Apr. 2013] His reign was one of busy diplomatic activity for the Vatican. The Church made advances on several fronts in the 1920s, improving relations with

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and, most spectacularly, settling the

Roman question

The Roman question (; ) was a dispute regarding the temporal power of the popes as rulers of a civil territory in the context of the Italian Risorgimento. It ended with the Lateran Pacts between King Victor Emmanuel III and Prime Minister Be ...

with Italy and gaining recognition of an independent Vatican state.

Pius XI's major diplomatic approach was to make

concordat

A concordat () is a convention between the Holy See and a sovereign state that defines the relationship between the Catholic Church and the state in matters that concern both,René Metz, ''What is Canon Law?'' (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1960 ...

s. He concluded eighteen such treaties during the course of his pontificate. However, wrote Peter Hebblethwaite, these concordats did not prove "durable or creditable" and "wholly failed in their aim of safeguarding the institutional rights of the Church" for "Europe was entering a period in which such agreements were regarded as mere scraps of paper".

[Peter Hebblethwaite; Paul VI, the First Modern Pope; HarperCollins Religious; 1993; p.118]

From 1933 to 1936 Pius wrote several protests against the Nazi regime, while his attitude to Mussolini's Italy changed dramatically in 1938, after Nazi racial policies were adopted in Italy.

Pius XI watched the rising tide of totalitarianism with alarm and delivered three papal encyclicals challenging the new creeds: against Italian Fascism ''

Non abbiamo bisogno

''Non abbiamo bisogno'' ( Italian for "We do not need") is a Roman Catholic encyclical published on 29 June 1931 by Pope Pius XI.

Context

The encyclical condemned what it perceived as Italian fascism's “ pagan worship of the State” ( sta ...

'' (1931; "We Do Not Need [to Acquaint You]"); against Nazism ''

Mit brennender Sorge

''Mit brennender Sorge'' ( , in English "With deep it. 'burning'anxiety") is an encyclical of Pope Pius XI, issued during the Nazi era on 10 March 1937 (but bearing a date of Passion Sunday, 14 March)."Church and state through the centu ...

'' (1937; "With Deep Concern"), and against atheist Communism ''Divini redemptoris'' (1937; "Divine Redeemer"). He also challenged the extremist nationalism of the

Action Française

''Action Française'' (, AF; ) is a French far-right monarchist and nationalist political movement. The name was also given to a journal associated with the movement, '' L'Action Française'', sold by its own youth organization, the Camelot ...

movement and

antisemitism in the United States

Antisemitism in the United States is the manifestation of hatred, hostility, harm, prejudice or discrimination against the American Jews, American Jewish people or Judaism as a Religion, religious, Ethnic group, ethnic or Race (human categorizat ...

.

Relations with France

France's republican government had long been anti-clerical, and much of the French Catholic Church anti-republican. The

1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State

The 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and State (French language, French: ) was passed by the Chamber of Deputies (France), Chamber of Deputies on 3 July 1905. Enacted during the French Third Republic, Third Republic, it establishe ...

had expelled many religious orders from France, declared all Church buildings to be government property, and had led to the closure of most Church schools. Since that time Pope Benedict XV had sought a rapprochement, but it was not achieved until the reign of Pope Pius XI. In ''Maximam gravissimamque'' (1924), many areas of dispute were tacitly settled and a bearable coexistence made possible.

In 1926, worried by the agnosticism of its leader

Charles Maurras

Charles-Marie-Photius Maurras (; ; 20 April 1868 – 16 November 1952) was a French author, politician, poet and critic. He was an organiser and principal philosopher of ''Action Française'', a political movement that was monarchist, corporatis ...

, Pius XI condemned the monarchist movement

Action Française

''Action Française'' (, AF; ) is a French far-right monarchist and nationalist political movement. The name was also given to a journal associated with the movement, '' L'Action Française'', sold by its own youth organization, the Camelot ...

. The Pope also judged that it was folly for the French Church to continue to tie its fortunes to the unlikely dream of a monarchist restoration, and distrusted the movement's tendency to defend the Catholic religion in merely utilitarian and nationalistic terms. Prior to this, Action Française had operated with the support of a great number of French lay Catholics, such as

Jacques Maritain

Jacques Maritain (; 18 November 1882 – 28 April 1973) was a French Catholic philosopher. Raised as a Protestant, he was agnostic before converting to Catholicism in 1906. An author of more than 60 books, he helped to revive Thomas Aqui ...

, as well as members of the clergy. Pius XI's decision was strongly criticized by Cardinal

Louis Billot

Louis Billot (12 January 1846 in Sierck-les-Bains, Moselle (department), Moselle, France – 18 December 1931 in Ariccia, Latium, Italy) was a French Jesuit priest and Theology, theologian. He became a cardinal in 1911 and resigned from that stat ...

who believed that the political activities of

monarchist

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. C ...

Catholics should not be censured by Rome. He later resigned from his position as Cardinal, the only man to do so in the twentieth century, which is believed by some to have been the ultimate result of Pius XI's condemnation,

though these claims have been disputed. Pius XI's successor, Pope Pius XII, repealed the papal ban on the group in 1939, once again allowing Catholics to associate themselves with the movement. However, despite Pius XII's actions to rehabilitate the group, ''Action Française'' ultimately never recovered to their former status.

Relations with Italy and the Lateran Treaties

Pius XI aimed to end the long breach between the papacy and the Italian government and to gain recognition once more of the sovereign independence of the Holy See. Most of the

Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

had been seized by the forces of King

Victor Emmanuel II

Victor Emmanuel II (; full name: ''Vittorio Emanuele Maria Alberto Eugenio Ferdinando Tommaso di Savoia''; 14 March 1820 – 9 January 1878) was King of Sardinia (also informally known as Piedmont–Sardinia) from 23 March 1849 until 17 March ...

of Italy (1861–1878) in 1860 at the

foundation of the modern unified Italian state, and the rest,

including Rome, in 1870. The Papacy and the Italian Government had been at odds ever since: the Popes had refused to recognise the Italian state's seizure of the Papal States, instead withdrawing to become

prisoners in the Vatican, and the Italian government's policies had always been

anti-clerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historically, anti-clericalism in Christian traditions has been opposed to the influence of Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, ...

. Now Pius XI thought a compromise would be the best solution.

To bolster his own new regime,

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

was also eager for an agreement. After years of negotiation, in 1929, the Pope supervised the signing of the

Lateran Treaties

The Lateran Treaty (; ) was one component of the Lateran Pacts of 1929, agreements between Italy under Victor Emmanuel III and Benito Mussolini and the Holy See under Pope Pius XI to settle the long-standing Roman question. The treaty and as ...

with the Italian government. According to the terms of the treaty that was one of the agreed documents,

Vatican City

Vatican City, officially the Vatican City State (; ), is a Landlocked country, landlocked sovereign state and city-state; it is enclaved within Rome, the capital city of Italy and Bishop of Rome, seat of the Catholic Church. It became inde ...

was given sovereignty as an independent nation in return for the Vatican relinquishing its claim to the former territories of the Papal States. Pius XI thus became a head of state (albeit the smallest state in the world), the first Pope who could be termed a head of state since the Papal States fell after the unification of Italy in the 19th century. The concordat that was another of the agreed documents of 1929 recognised Catholicism as the sole religion of the state (as it already was under Italian law, while other religions were tolerated), paid salaries to priests and bishops, gave civil recognition to church marriages (previously couples had to have a civil ceremony), and brought religious instruction into the public schools. In turn, the bishops swore allegiance to the Italian state, which had veto power over their selection. The Church was not officially obligated to support the Fascist regime; the strong differences remained, but the seething hostility ended. Friction continued over the

Catholic Action

Catholic Action is a movement of Catholic laity, lay people within the Catholic Church which advocates for increased Catholic influence on society. Catholic Action groups were especially active in the nineteenth century in historically Catholic cou ...

youth network, which Mussolini wanted to merge into his

Fascist youth group.

The third document in the agreement paid the Vatican 1.75 billion

lira

Lira is the name of several currency units. It is the current Turkish lira, currency of Turkey and also the local name of the Lebanese pound, currencies of Lebanon and of Syrian pound, Syria. It is also the name of several former currencies, ...

(about $100 million) for the seizures of church property since 1860. Pius XI invested the money in the stock markets and real estate. To manage these investments, the Pope appointed the lay-person

Bernardino Nogara, who, through shrewd investing in stocks, gold, and futures markets, significantly increased the Catholic Church's financial holdings. The income largely paid for the upkeep of the expensive-to-maintain stock of historic buildings in the Vatican which until 1870 had been maintained through funds raised from the Papal States.

The Vatican's relationship with Mussolini's government deteriorated drastically after 1930 as Mussolini's totalitarian ambitions began to impinge more and more on the autonomy of the Church. For example, the Fascists tried to absorb the Church's youth groups. In response, Pius issued the encyclical ''

Non abbiamo bisogno

''Non abbiamo bisogno'' ( Italian for "We do not need") is a Roman Catholic encyclical published on 29 June 1931 by Pope Pius XI.

Context

The encyclical condemned what it perceived as Italian fascism's “ pagan worship of the State” ( sta ...

'' ("We Have No Need)" in 1931. It denounced the regime's persecution of the church in Italy and condemned "pagan worship of the State." It also condemned Fascism's "revolution which snatches the young from the Church and from Jesus Christ, and which inculcates in its own young people hatred, violence and irreverence".

From the earliest days of the Nazi takeover in Germany, the Vatican was taking diplomatic action to attempt to defend the Jews of Germany. In the spring of 1933, Pope Pius XI urged Mussolini to ask Hitler to restrain the anti-Semitic actions taking place in Germany. Mussolini urged Pius to excommunicate Hitler, as he thought it would render him less powerful in Catholic Austria and reduce the danger to Italy and wider Europe. The Vatican refused to comply and thereafter Mussolini began to work with Hitler, adopting his anti-Semitic and race theories. In 1936, with the Church in Germany facing clear persecution, Italy and Germany agreed to the

Berlin-Rome Axis.

Relations with Germany and Austria

The Nazis, like the Pope, were unalterably opposed to Communism. In the years leading up to the 1933 election, the German bishops opposed the

Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

by proscribing German Catholics from joining and participating in it. This changed by the end of March after Cardinal

Michael Von Faulhaber

Michael von Faulhaber (5 March 1869 – 12 June 1952) was a German Catholic prelate who served as list of bishops of Freising and archbishops of Munich and Freising, Archbishop of Munich and Freising for 35 years, from 1917 to his death in 195 ...

of Munich met with the Pope. One author claims that Pius expressed support for the regime soon after Hitler's rise to power, with the author asserting that he said, "I have changed my mind about Hitler, it is for the first time that such a government voice has been raised to denounce Bolshevism in such categorical terms, joining with the voice of the pope."

A threatening, though initially sporadic persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany followed the 1933 Nazi takeover in Germany. In the dying days of the

Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

, the newly appointed Chancellor

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

moved quickly to eliminate

political Catholicism

The Catholic Church and politics concerns the interplay of Catholicism with religious, and later secular, politics.

The Catholic Church's views and teachings have evolved over its history and have at times been significant political influences ...

. Vice Chancellor

Franz von Papen

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, (; 29 October 18792 May 1969) was a German politician, diplomat, Prussian nobleman and army officer. A national conservative, he served as Chancellor of Germany in 1932, and then as Vice-Chancell ...

was dispatched to Rome to negotiate a

Reich concordat

The ''Reichskonkordat'' ("Concordat between the Holy See and the German Reich") is a treaty negotiated between the Vatican and the emergent Nazi Germany. It was signed on 20 July 1933 by Cardinal Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli, who later be ...

with the Holy See.

Ian Kershaw

Sir Ian Kershaw (born 29 April 1943) is an English historian whose work has chiefly focused on the social history of 20th-century Germany. He is regarded by many as one of the world's foremost experts on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, and is ...

wrote that the Vatican was anxious to reach an agreement with the new government, despite "continuing molestation of Catholic clergy, and other outrages committed by Nazi radicals against the Church and its organisations". Negotiations were conducted by Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, who later became

Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII (; born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli; 2 March 18769 October 1958) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death on 9 October 1958. He is the most recent p ...

(1939–1958). The ''Reichskonkordat'' was signed by Pacelli and by the German government in June 1933, and included guarantees of liberty for the Church, independence for Catholic organisations and youth groups, and religious teaching in schools. The treaty was an extension of existing concordats already signed with

Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

and

Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

, but, wrote Hebblethwaite, it seemed "more like a surrender than anything else: it involved the suicide of the

atholic Centre Party... ".

"The agreement", wrote

William Shirer

William Lawrence Shirer (; February 23, 1904 – December 28, 1993) was an American journalist, war correspondent, and historian. His '' The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich'', a history of Nazi Germany, has been read by many and cited in schol ...

, "was hardly put to paper before it was being broken by the Nazi Government". On 25 July, the Nazis promulgated their

sterilization law, an offensive policy in the eyes of the Catholic Church. Five days later, moves began to dissolve the Catholic Youth League. Clergy, nuns and lay leaders began to be targeted, leading to thousands of arrests over the ensuing years, often on trumped up charges of currency smuggling or "immorality".

[William L. Shirer; The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich; Secker & Warburg; London; 1960; p234-5]

In February 1936, Hitler sent Pius a telegram congratulating the Pope on the anniversary of his

coronation

A coronation ceremony marks the formal investiture of a monarch with regal power using a crown. In addition to the crowning, this ceremony may include the presentation of other items of regalia, and other rituals such as the taking of special v ...

, but Pius responded with criticisms of what was happening in Germany so forcefully that the German foreign secretary

Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin Hermann Karl Freiherr von Neurath (2 February 1873 – 14 August 1956) was a German politician, diplomat and convicted Nazi war criminal who served as Foreign Minister of Germany between 1932 and 1938.

Born to a Swabian noble famil ...

wanted to suppress the response, but Pius insisted it be forwarded to Hitler.

Austria

The pope supported the

Christian Social Party in

Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, a country with an overwhelmingly Catholic population but a powerful secular element.

[William L. Shirer; The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich; Secker & Warburg; London; 1960; pp. 349–350.] He especially supported the regime of

Engelbert Dollfuss